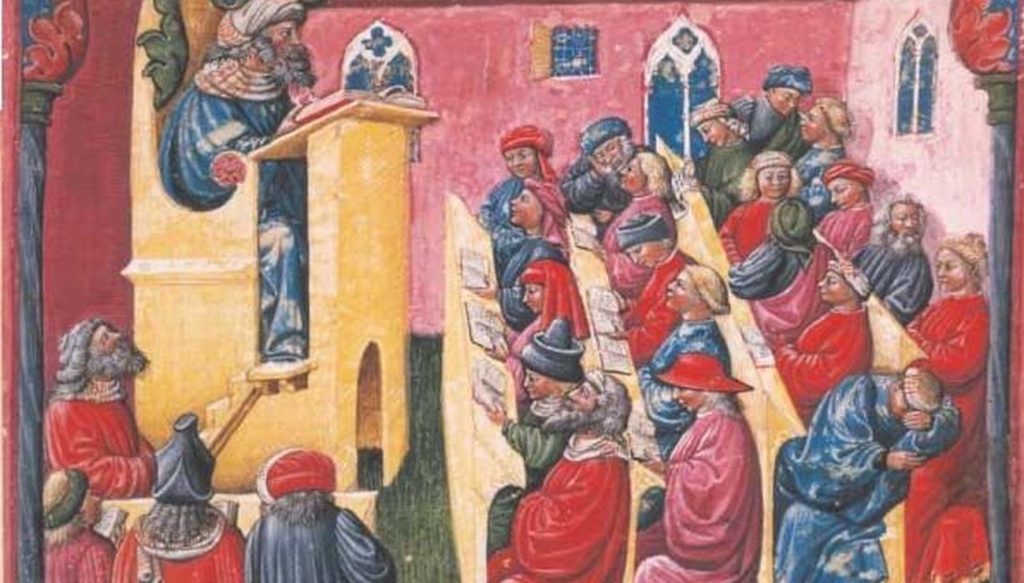

Universities in the Middle-Ages, , though having gone through many reforms during the centuries since their apparition, were remarkably similar to modern institutions, as it possess a student body, teachers, a rector and staff. Where they differ is in the degree of independance and self-governance: the government of the university is a representative government. The University of Franche-Comté was, following the example of its predecessors, a free body having its leader, its officers, its budget, its justice, administering itself, governing itself by its own laws, or reforming its statutes. The sense of community of the university is solidified by the way it “speaks” in texts, starting or concluding in the name of “the rector, doctors, regents, suppôt, students”.

The rector, ancestor of the directors

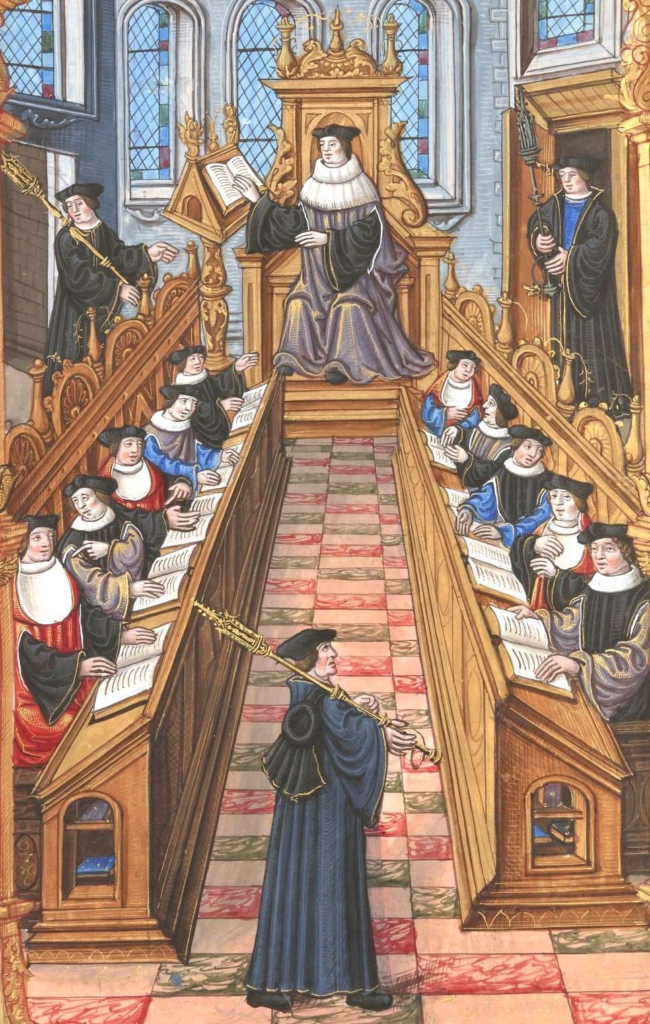

The structural organization of the university was patterned around those of its predecessors. The head of the University bore the name of rector, which is found, from Roman times, to designate the head of a corporation, the governor of a province, the podesta in the Italian cities of the Middle Ages, etc. The rector represented the University as a corporation. He was assisted by the peoples in charge of the administration, who had the heavy duty of managing finances, recruit teachers, maintain the buildings, etc. His presence was deemed so essential within the school that he was forbidden to be absent for more than a month without a legitimate reason, and for the same reason, to exercise the profession of lawyer or prosecutor. He had custody of the seal, the presidency of all university solemnities, general assemblies and scholastic acts, and precedence over the bishops, side by side with the head of parliament.

Students had great power

The students had a greater influence than in other universities on its functioning. At Dole, the students took part, within a certain limit, in the administration. Not only do they elect by direct suffrage the procurators and councilors of the university, but the important decisions taken by the college, that is to say by the grand council, must be submitted to their approval. The noble-born students had more power among their peers as they could participate in the discussions rather than simply vote upon the decisions taken. Also, the rector could be a student, with some conditions preventing anyone to be elected, such as being at least 25 years old, being from a legitimate union, and depending on the university financially.

Those who are rarely mentionned

On the side of the staff, the distributors were responsible of the administration on the financing side, with the recruitment of the teachers, the varied fees like embassies, maintenance of the buildings, etc. The beadle, went every morning to take the rector’s instructions in his residence, preceded him in public ceremonies, a mass of silver or a green rod in his hand, indicated to each his place in the processions and in the examinations, published the day of the disputes, the order of the questions and the subjects which would be treated there, warned the students by posters of the beginning and the end of the holidays, of the public holidays, of the opening of the extraordinary courses, of the arrival of the foreign teachers, etc. A secretary, appointed by the college, was responsible for drawing up, under the supervision of the rector, the deliberations of the council and of the general assemblies, of sending out the diplomas, of writing and countersigning the letters of order, the schedules of the head of the university, etc. The university finally had a bellringer, who announced readings and other public acts by the sound of the bell.